Thumbnail is a segment from This Outfit Does Not Exist. As a complement to my subscriber-only deep dives, thumbnails are a shorter, more personalised, set of musings on the future of digital culture. If this sounds exciting please:

This week’s thumbnail is written from London, where I’ve spent the past 28 hours trying outfits on an AI generated version of myself. At time of writing my outfit count totals 487.

The thumbnail

The German novelist Jean Paul coined the term doppelgänger in 1796.

The word refers to the idea of a spirit double that’s identical to a living person — something humans have fabulated, and feared, for millennia.

From tales of the Norse Vardøger (a ghostly double who performs a person's actions in advance), to movies like Us, a doppelgängers’ narrative arc most frequently plays on the human fear of an identical being that displaces, and then replaces, us.

Yet there is irony in doppelgängerdom.

As psychologist Donn Byrne argues in his ‘similarity-attraction theory’, while the term doppelgänger points to our fear of substitution, we also hold higher levels of attraction, trust, and comfort to those who look like us.

Which begs the question: when our online world becomes populated by digital doubles will we lock in, or run out?

The double click

I first entertained the prospect of widespread digital doppelgängerdom when I discovered Rosebud in late-2018. Now pivoted beyond recognition, the company began as a synthetic media startup using AI to generate personalised models for ads, and when I say models I don’t meant LLMs1. Rather Rosebud’s mission was to create simulated humans with features that responded to what each advertisee would find compelling.

To give examples of what this looks like in practice, in a post-Rosebud world you’re on YouTube and a Dove commercial comes on—only the girl in the ad has exactly your hair, if not your features. When Instagram suggests you download Tinder or Hinge the sultry stare that draws you in is given by someone who’s exactly your type. When you’re buying clothes on Net-a-Porter the model trotting across the product page is you (only slightly better dressed), and when you’re debating getting that Equinox membership the person you see determinedly squatting is you, with the body you envision.

While Rosebud’s combination of AI-generated personalisation and virtual models hasn’t yet reached the mainstream, the personalised consumer internet is something we interact with on a daily basis. In its most talked about form there’s TikTok, whose algorithmic tailoring is lauded for its abilities to surprise and delight, and Instagram which I am still convinced is listening to me based on the ads it suggests. However, less well-known is Netflix, which began algorithmically tailoring its thumbnails back in 2017 to encourage click-throughs on a user-by-user basis.

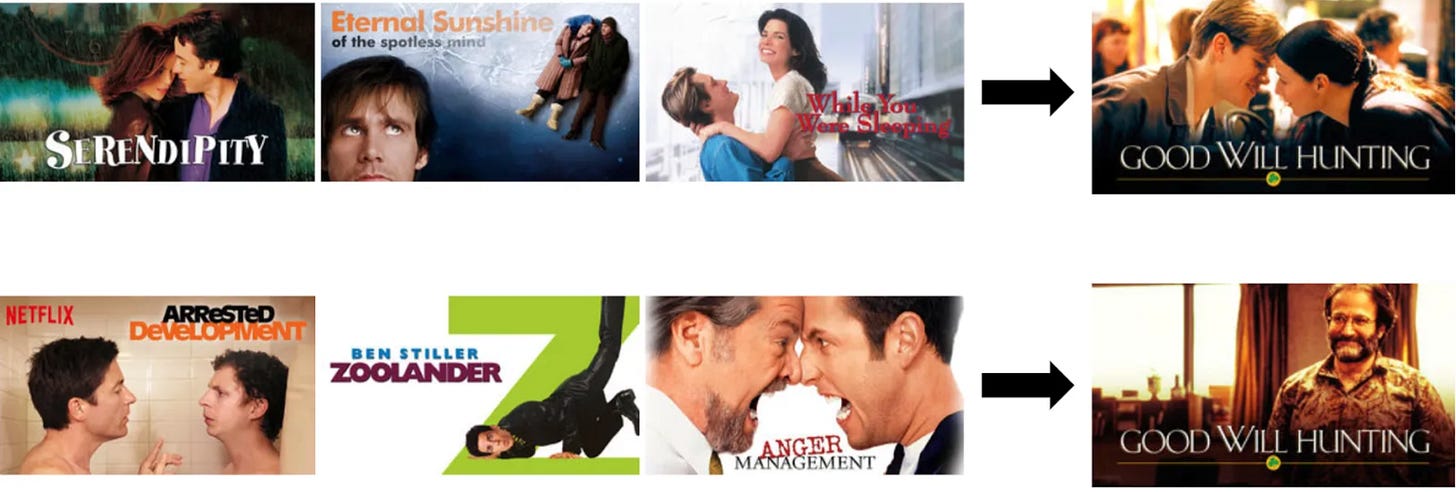

Go to your Netflix account and search for a movie. Then go to your best-friend’s/ ex’s account and search for the same thing. The cover images representing each film will most likely be different depending on which account you view them from. This is because Netflix uses Aesthetic Visual Analysis2 to personalise how it displays content. If you’re a big romcom watcher your Goodwill Hunting thumbnail will be generated to show Will and Skylar sharing a kiss. If you’re a fan of comedy you’re more likely to see a grinning Sean, played by Robin Williams. The personalised consumer internet takes this same idea of tailoring product discovery and applies it to every single sector, including fashion.

A few months ago, I was contacted by a friend, Dorian Dargan around how a hyper-personalized fashion-internet could look. Dorian was founding Doji, a new startup which allows you to ‘create your likeness, try-on products and explore new looks.' Yet although Dorian and his cofounder are as close to a dream team as you can get, I started off skeptical for three reasons:

The virtual try-on market has a two-decade history of failure — clothing returns are a $218 billion problem, meaning budding founders and tech mammoths alike have been fighting to crack virtual try-on for 20+ years, with limited success. EZface (now closed) pioneered Augmented Reality (AR) mirrors at the turn of the millennia, Converse implemented AR try-on back in 2012 and SNAP acquired Fit Analytics, Vertebrae and Ariel AI in 2021. Yet I’d bet not one of you regularly uses virtual try-on today.

With the rise of generative AI the virtual try-on space is becoming less and less defensible — after spending 10+ years, and billions of dollars, to become virtual try-on’s market leader SNAP CEO Evan Spiegel announced that he was planning to shut-down ARES— SNAP’s AR enterprise services unit—after just 6 months. His justification: “the rise of generative AI has made it tougher for SNAP to stand out as a leader in the virtual try-on market.” If the company that onboarded Prada and Farfetch into the virtual try-on space doesn’t think it has the ability to defend its position, what hope does a seed stage company have to create a lasting moat?

Size-and-fit accuracy remain unsolved — as every fashion product differs in tailoring, and each body is completely different, virtual try-on to date has remained a largely cosmetic solution. While seeing how a certain colour/ style looks is undoubtedly valuable, 70% of returns are due to size-and-fit issues. If a startup cannot resolve this challenge3 it makes it far harder to provide tangible value, as has been shown through the failed AR solutions of the past.

Despite all the arguments above, since getting access to Doji’s private beta all I’ve done is Doji: I’ve Dojied at work, I’ve Dojied before bed, I even Dojied on a date with my boyfriend (who has since downloaded Doji). Once I uploaded the 8 selfies (taken on the spot) and two full-body pics (extracted from camera roll) needed to create my Doji avatar, I was transformed from a virtual-try on skeptic, to a virtual-try on convert with evangelical hope for not only the technology but the product itself.

So what makes Doji different?

We are rapidly moving into an age where technology is no longer what makes a product defensible. The ever-improving suite of AI tools like GPT 4 and Cursor are lowering the barriers to who can be a builder to the extent that even I vibe-code on the weekends.

In a world where one of the deepest moats you could previously erect is now overrun with generative drawbridges, what is left to defend the fort of hardware-less consumer products? Put simply, network.

I was first drawn to digital fashion for its ability to make me feel beautiful. Every time I got sent back a digitally dressed picture from a company like Tribute Brand I’d feel such a rush of joy at my transformation that my posts would be preceded by a slew of annoying whatsapps to my closest friends and family demanding they “look at me!” immediately.

Doji elicits this same wave of egomania through its creation of what my boyfriend and I refer to as ‘hot Dani’— aka. my Doji avatar. The beauty of ‘hot Dani’ is that she is indistinguishable from me (normal Dani) at first glance, but on close inspection is taller, skinner and just generally better looking. The genius of this strategy is that it assuages the user on two fronts:

It encourages sharing because as Facetune and filters have proven, you want to show the world a better looking version of you and are just searching for a vessel that allows this narcissism to be socially sanctioned.

It encourages buying by selling you the fantasy of aesthetic improvement you’d formerly feel when gazing at a glamorous model. Only now that model is you.

At only a few months old Doji’s retention capabilities still remain to be seen, but data points ranging from: 1)

’s ‘selfie thesis’– where he posits that any product or service that makes us look better in a selfie, or on Zoom, has tailwinds behind it 2) Lighttricks’4 $1 billion valuation and 3) the myth of Narcissus — who died gazing at his own reflection, I’d argue that the human condition is set in Doji’s favour.The zoom out

In my essay Changing Faces I wrote about the permissions online spaces give us to occupy entirely new bodies, and the freedom we have when decoupled from IRL forms. But when the form occupied is not alien mass but simulated human, and we spend our screen time gazing into a san-serifed pool of personalised perfection, will we become hyper-aware of the LARP which is the ‘algorithmic glow up’? Or will we, like Narcissus, die by the image that we so badly desire but will never have?

Coralie Fargeat’s award winning movie The Substance suggests the latter— telling the tale of an aging fitness icon. Nearing the end of a successful career protagonist ‘Elisabeth Sparkle’ discovers an optimisation drug known as ‘The Substance’ that allows her to revert back to a younger, hotter version of herself. Much like our digital-physical dichotomies Sparkle is unable to take the form of her double consistently, and is instructed to regress back to her original form every-other day. However the obsession with her new, perfected, anatomy soon gets the better of her and she refuses to revert back as per the instructions. The result? A hideously disfigured monster.

For those who perceive The Substance as mere futuristic fable, the jarring existence of ‘Filter Face’ reveals its reality. For her 2019 expose in The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino explores the prevalence of plastic surgery requests to replicate filter/facetune-induced enhancements. Tolentino concludes that in a post-digital dysmorphic world: ‘For those born with assets—natural assets, capital assets, or both—it can seem sensible, even automatic, to think of your body the way that a McKinsey consultant would think about a corporation: identify underperforming sectors and remake them, discard whatever doesn’t increase profits and reorient the business toward whatever does’.

While the encroachment of digital dysmorphia is highly disruptive on an individual level— with 30% of clients visiting one of Tolentino’s surgeons coming armed with photos of Kim Kardashian as inspo —the hyper-personalised consumer internet raises even broader sociological concerns.

Many argue that the internet has become detrimental to debate as algorithms herd us into siloes of interaction with those who share our views. These echo chambers have long been explored when it comes to our politics, but what happens when they spill into our aesthetics too? If our online experience is solely populated with images of us, or of those we find compelling, how will this change the ways we conceptualise the divergent or diverse? In the same way that some claim the internet has reduced our capacity to engage with those who hold differing views, will all this aesthetic tailoring lead to a reduced tolerance for those we aren’t visually compelled by?

To diverge from the synthetically stimulated sadness for a sec, while digital doppelgängerdom presents potential to further the economy of discontent, it can also disrupt aspirational behaviours by introducing elements of democracy. As I’ve written about extensively, digital fashion presents the ability to flatten online culture by allowing anyone to freely express, regardless of their financial limitations. Using Doji I can create content of myself wearing a $3,000 coat from Rick Owens, Dior boots that just went down the catwalk, and even Balenciaga couture, for $0. In this post-tariff world, this is increasingly valuable. Plus if the ability to afford a look is no longer what clout is contingent on, an optimist might see online status being reframed around creativity. Here’s hoping.

— Dani

A large language model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence (AI) that can process, understand, and generate human language. LLMs are used in many industries to analyze, summarize, and create content

AVA is a collection of tools and algorithms designed to quickly and effectively identify which frames are the best moments to represent a title on the Netflix service

Note — this is on the Doji product roadmap

The company behind Facetune

wonderful thoughts

Love this synopsis!!